Welcome to the Learning Design and Technology team’s starter guide for teaching online. We have prepared this page for faculty interested in exploring digital modalities. You will find information on the principles that drive the LDT team’s work, as well as resources for adapting your content for alternative delivery. If you would like to discuss digital learning further, please contact the Learning Design and Technology team.

Table of Contents

⏵ PRINCIPLES OF ONLINE COURSES

┄‣ Introduction

┄‣ Backward Design

┄‣ Scaffolding

┄‣ Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

⏵ RESOURCES FOR TEACHING ONLINE

┄‣ Course Staff Knowledge Base

┄‣ Computing and Educational Technology Services (CETS)

┄‣ Center for Excellence in Teaching, Learning, and Innovation (CETLI)

┄‣ Canvas Info @Penn

Principles of Online Courses: Backward Design, Scaffolding, and UDL

Introduction

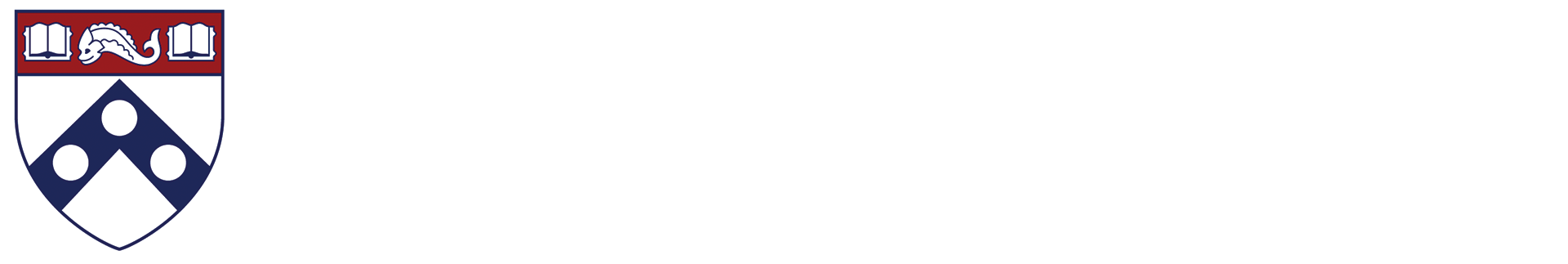

Creating effective online courses involves careful planning to ensure students can achieve the learning objectives and stay engaged. Three key principles can help educators design impactful online learning experiences: Backward Design, Scaffolding, and Universal Design for Learning (UDL). These approaches focus on clear goal-setting, structured support, and belonging, which are essential for student success in a virtual environment.

Backward Design

In online courses, students often navigate content and activities on their own schedule. To help them stay focused, it’s important to make the learning goals clear and show how the content and assignments connect to those goals.

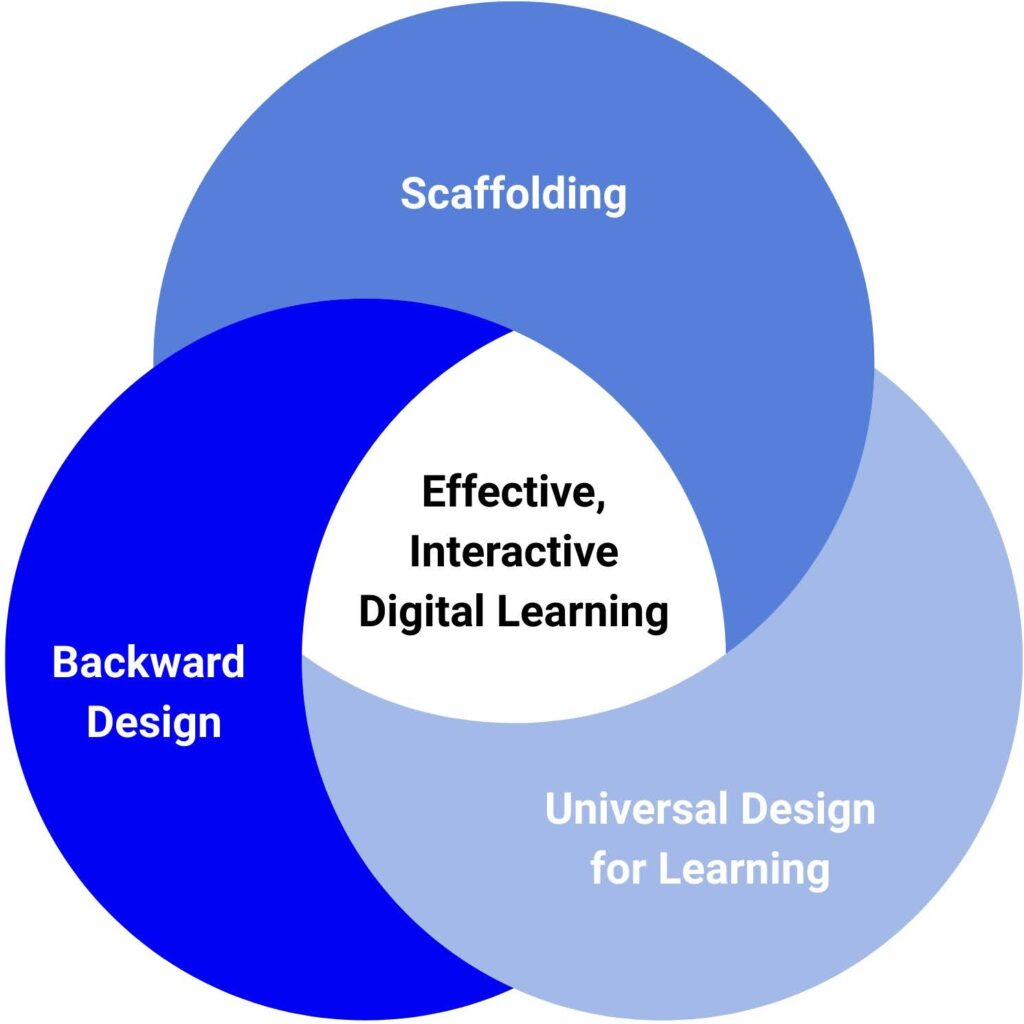

Backward Design is a method where you start by identifying what you want students to know or be able to do (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). Then, you organize all aspects of the course—lectures, activities, quizzes, homework, discussion posts—to guide students toward achieving those outcomes.

⏵ In this diagram by a Senior Instructional Designer, the faculty’s idea for a final project dictated the preceding homeworks, and led to helping define lecture topics, low-stakes quiz opportunities and lessons on the coding languages involved in the project.

Scaffolding

Scaffolding involves creating steps that help students reach the course goals you’ve set (Reiser, 2004). While guiding students toward larger goals is useful in any setting, it’s especially important online, where they may lack immediate support and feedback from you and their peers.

By building regular opportunities for practice and feedback into your course, you provide students with indicators of their progress (Belland, Kim, & Hannafin, 2013).

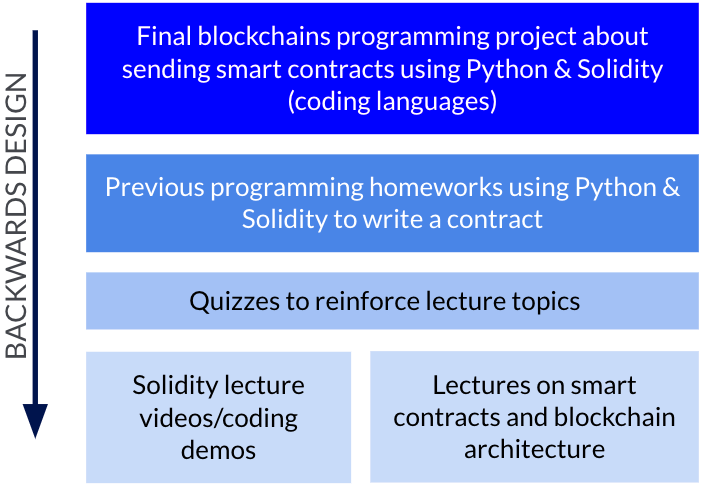

Including brief module or unit overviews—whether at the beginning of each module, at key midpoints, or as summary reflections—can also serve as helpful scaffolds. These overviews give students a sense of the course structure and progression, which online learners consistently find clarifying and motivating.

Other effective strategies include using low-stakes multiple-choice quizzes with detailed, automated feedback to help students gauge their understanding of the material. Breaking content into short, purposeful segments also helps align goals with student work and keeps their attention focused.

⏵ In this screenshot of an online course, the content is broken down into smaller pieces. Each module has multiple lessons, and each lesson has many short videos that allow a busy online learner to start, stop, and return to their learning at their own convenience without getting lost.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

UDL is a framework that aims to optimize teaching and learning by offering flexible ways for students to access content, engage with material, and demonstrate knowledge (CAST, 2024). By providing multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement, UDL addresses varied learning abilities and backgrounds, ensuring opportunities for success for all.

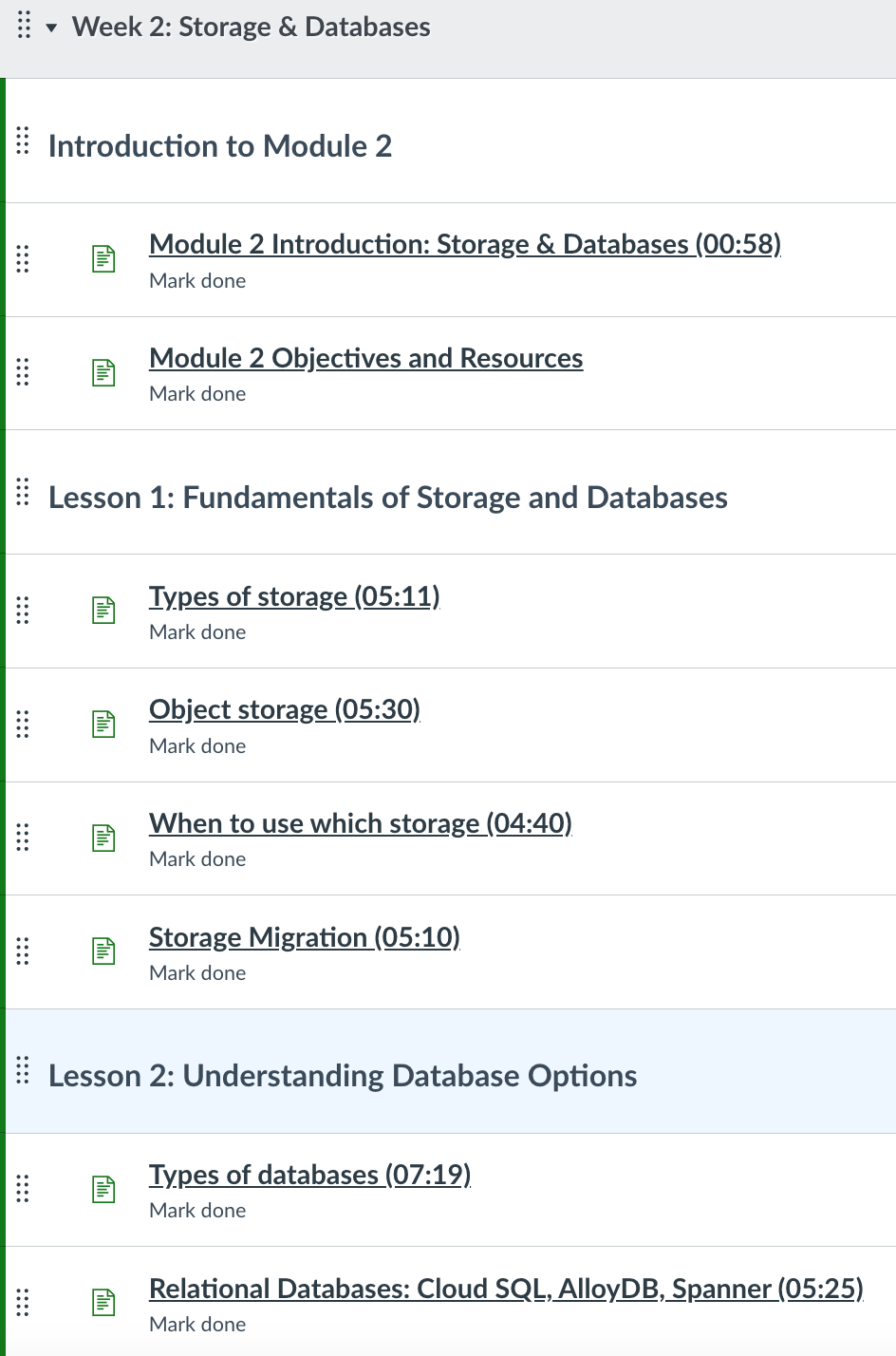

In online learning, UDL enhances belonging and accessibility. You can apply UDL principles by presenting content in various formats—text, audio, and video—to cater to different learning preferences. Providing transcripts for video lectures, captions for audio materials, and descriptive text for images makes content accessible to all students, including those with disabilities.

Allowing students to choose how they demonstrate their understanding—through essays, presentations, videos, or projects—also supports a variety of learners (Moore, 2007). Incorporating interactive elements like quizzes, discussion forums, and multimedia resources keeps students engaged and actively involved.

⏵ In this screenshot of an online course, the lecture content is represented through multiple means, including audio, visual, and textual formats.

Resources for Teaching Online

In addition to seeking our support, be sure to explore these other teaching and learning resources.

Course Staff Knowledge Base

If you currently teach with Penn Engineering Online and are looking for specific or advanced help with an instructional tool, we recommend you explore the Course Staff Knowledge Base curated by the LDT team. It includes helpful articles, as well as information on Course Staff Onboarding.

Computing and Educational Technology Services (CETS)

Computing and Educational Technology Services (CETS) provides computing support and related educational services to the students, faculty, and staff of Penn Engineering and serves as the primary contact for instructional technology questions and support.

Center for Excellence in Teaching, Learning, and Innovation (CETLI)

Penn’s Center for Excellence in Teaching, Learning, and Innovation (CETLI) has a wealth of resources for faculty across the university. They run frequent workshops on online teaching, with topics such as creating community, instructional technologies, facilitating live sessions, and more.

Canvas Info @Penn

The Canvas Info @Penn site is a central source of information about Canvas, Penn’s learning management system, and related technologies at the university. The site supports the Courseware needs of faculty, TAs, students, and staff. For questions or assistance, contact canvas@pobox.upenn.edu.

References

Belland, B. R., Kim, C., & Hannafin, M. J. (2013). A framework for designing scaffolds that improve motivation and cognition. Educational Psychologist, 48(4), 243–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2013.838920

CAST. (2024). Universal Design for Learning guidelines version 3.0. https://udlguidelines.cast.org

Moore, S. (2007). David H. Rose, Anne Meyer, Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal Design for Learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 55, 521–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-007-9056-3

Reiser, B. J. (2004). Scaffolding complex learning: The mechanisms of structuring and problematizing student work. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(3), 273–304. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1303_2

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). ASCD. https://www.perlego.com/book/3292673/understanding-by-design-pdf